Last week, the TR Site kicked off its 2016 Speaker Nite series by welcoming historian Martin S. Nowak, author of The White House in Mourning. His presentation focused on the eight American presidents who died in office: William Henry Harrison (1841); Zachary Taylor (1850); Abraham Lincoln (1865); James A. Garfield (1881); William McKinley (1901); Warren G. Harding (1923); Franklin D. Roosevelt (1945); and John F. Kennedy (1963).

Mr. Nowak began his remarks by providing some perspective – the majority of people living in the United States today were born after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and therefore have no first-hand memory of a president dying in office. Yet, between 1841 and 1963, approximately one-third of the men elected to the office of president died while holding that title. Put another way -- someone born in 1841, who lived to be 83 years old, would have “seen" six presidents die during their lifetime.

The death of a president, Mr. Nowak reminded the audience, is not only a national tragedy. Each of the presidents who died in office left behind family and friends to cope with an intensely personal loss, played out on a public stage. For example, when John F. Kennedy was killed in 1963, he was survived by his wife, two children, two brothers, four sisters, both parents, and his maternal grandmother.

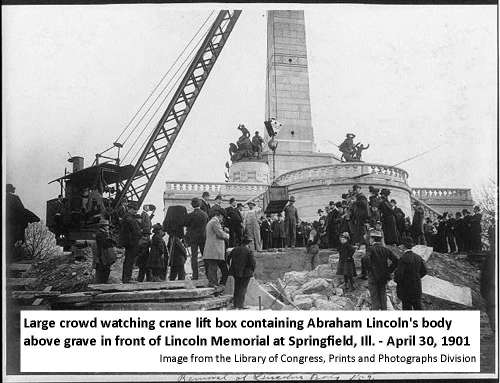

Presidential funerals are a combination of public and private ceremony and have varied widely over the years. In the midst of World War II, Franklin Roosevelt was buried only three days after his death. By contrast, a funeral train carrying Abraham Lincoln’s body traveled through 180 cities and seven states – more than 1,600 miles –– before arriving in Springfield, Illinois, nearly three weeks after his assassination. The train stopped in major cities (like Buffalo) along its route from Washington, DC. At each stop, the coffin was removed from the train, conveyed to a public hall, opened, and Lincoln’s body lay in state to allow the people to pay their respects. Even after his burial in Springfield, Lincoln didn’t exactly rest in peace. Over the next thirty-six years, it is estimated that Lincoln’s body was moved seventeen times! It was not until September 26, 1901 (coincidentally, one week after President William McKinley’s burial) that Lincoln’s body was entombed in a ten-foot deep hole and covered with cement. This was done at the request of Lincoln’s son, Robert, and his father’s remains have not been disturbed since.

Although the case of Abraham Lincoln’s posthumous movements is remarkable because of its repetition, all but one of the other presidents who died in office were initially buried in a temporary location. In most cases, this allowed for the financing and construction of a suitable monument. Franklin Delano Roosevelt is the only president who died in office and whose body has not been moved since he was buried.

Like Franklin Roosevelt, William Henry Harrison’s death was attributed to “natural causes”. Harrison was inaugurated on a cold March day in 1841 and afterwards delivered a nearly two hour inaugural address – outside, wearing neither coat nor hat. Soon thereafter, he developed pneumonia and doctors were called in. Harrison received treatment according to the standards of the time, which included cupping as well as the administration of cathartics (such as calomel, castor oil, and rhubarb). He was also given ipecac, laudanum, camphor, wine whey, and brandy. The doctors’ best efforts left the president very weak, jaundiced, and dehydrated. Whether Harrison might have survived in the absence of these “treatments” is subject to speculation, but ultimately they did more harm than good and certainly hastened the president’s demise.

Forty years after Harrison’s death, doctors’ ministrations may have also played a role in the death of President James A. Garfield. When Charles Guiteau shot Garfield on July 2, 1881, the bullet did not damage any internal organs. However, rather than leaving the bullet inside the president (a reasonable option), Garfield’s doctors obsessively tried to locate and remove it. Germ theory was not widely accepted at the time, so when the doctors probed Garfield’s wound, they used bare fingers and unsterilized equipment. They never found the bullet, but in all likelihood introduced the infection and brought about the blood poisoning that ultimately killed the 20th president. Even Charles Guiteau asserted, “Yes, I shot him, but his doctors killed him.”

In the case of Garfield’s death – and Lincoln’s sixteen years earlier – another contributing factor was certainly the lack of formal presidential protection. Established shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, the Secret Service had nothing to do with protecting the president or anyone else at the time; it was created to combat the widespread problem of counterfeit currency. Its initial foray into presidential protection did not come until 1894, when it was investigating a group of gamblers and discovered a plot to assassinate President Cleveland. The resulting informal, part-time protection detail was discontinued after only a short time. During William McKinley’s presidency, which coincided with the Spanish-American War and fears brought about the anarchist movement, the Secret Service stepped up its protection duties, but the arrangement was still very casual. It wasn’t until after McKinley’s assassination that Congress informally asked for the president to be protected. In 1902, the Secret Service assumed full-time responsibility for protecting President Theodore Roosevelt. It was several years, however, before Congress allocated funds for presidential protection. Permanent protection of the president was authorized in 1913, but the law had to be renewed every year until 1951.

Mr. Nowak concluded his remarks with a brief overview of the eight vice presidents who ascended to the presidency upon the death of their predecessors:

He went on to highlight some of the political differences between the pairs (for example, Millard Fillmore signed the Compromise of 1850, even though his predecessor opposed it) and left the audience pondering the long-term implications of a president’s death.

--Lenora Henson, Curator

____________________

Image from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. ~ http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005684967/

*****

Speaker Nite is part of the TR Site’s regular Tuesday evening programming, which is made possible with support from M&T Bank.

The Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site is operated by the Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Site Foundation, a registered non-profit organization, through a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

© 2026 | All Rights Reserved

641 Delaware Avenue, Buffalo, NY 14202 • (716) 884-0095

Website by Luminus